Crimes against journalists go unpunished, freedom of speech targeted

Written by: Jelena L. Petković, Safe journalists/Bezbedni novinari (published – 28th, decembar, 2022)

It has been 22 years since journalist Marjan Melonaši became the victim we describe using the term – missing.

He was 24 years old. He was 179 centimeters tall, with wavy brown hair, green eyes, studied English language at the University of Priština, and was planning to get married. He was an only child, and he had many friends.

At two o’clock in the afternoon, on 9 September 2000, he finished his half-hour broadcast on the Serbian desk of Radio Kosovo. He left the studio in the centre of Priština and got into an orange taxi. People working across the street saw him.

That is the last information the family knows about Marjan Melonaši.

Marjan was previously employed by the Swiss organization “Media Action International”. Shortly before his arrival, another journalist had worked in that organization, whose name would be on the list of missing persons for two years, and then it would be known that he was killed.

Journalist and translator Aleksandar Simović Sima was kidnapped together with his Albanian friend on 21 August 1999 in Priština. They were kidnapped by “people in black uniforms with red markings on their sleeves and took them in an unknown direction”, UNMIK will note.

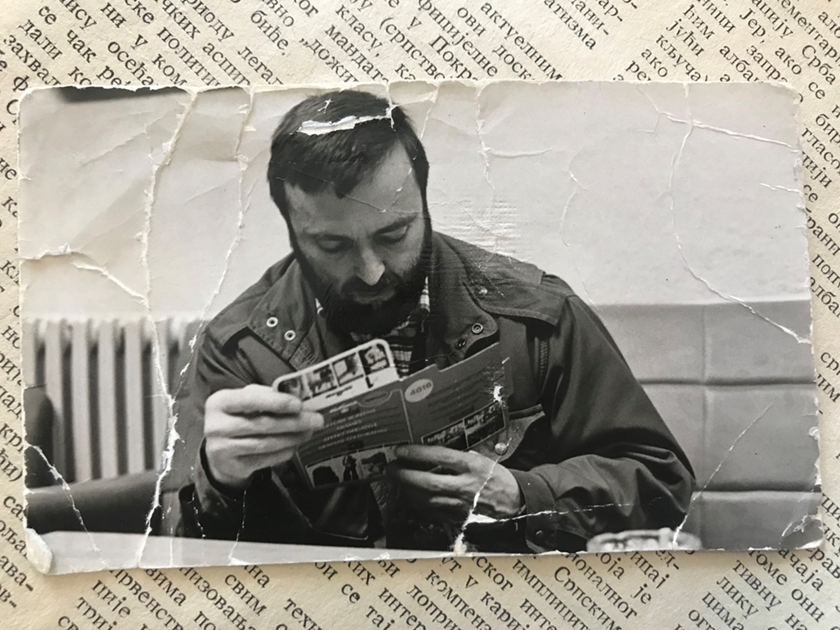

Just before the war, Aleksandar studied at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, and then worked at the Centre for Peace and Tolerance. In addition to music and chess, he loved to read and was a talented writer. Two of his books were published posthumously.

The remains of Aleksandar Simović Sima were found on 8 June 2001 in a forest near Glogovac.

The names of the two young journalists are part of a tragic list of crimes that have never been investigated. While performing their journalistic work, between 1998 and 2005 – 20 Albanians and Serbs, journalists and media workers, as well as a three-member crew of the German magazine Stern were killed, kidnapped or missing in Kosovo.

Only one of those crimes, the murder of Professor and translator Šaban Hoti, who was captured as part of a Russian journalists’ team, was prosecuted before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

Journalist Ismail Berbatovci disappeared on 23 July 1998, when he went on a journalistic assignment.

Đura Slavuj and Ranko Perenić, the journalists’ team of Radio Priština, disappeared when they went on a journalistic assignment on 21 August 1998 near Velika Hoča.

Journalist Nebojša Radošević and photographer Vladimir Dobričić were kidnapped during their work assignment on 18 October 1998 near Priština. They were released 41 days later.

Journalist Afrim Maliqi was killed on 2 December 1998 in Priština.

Journalist and Head of the Kosovo Information Center (KIC) Enver Maloku was killed on 11 January 1999 in Priština.

Correspondent of the daily “Politika” and a journalist of “Jedinstvo” from Priština Ljubomir Knežević disappeared on 6 May 1999 in Vučitrn.

Two journalists from the German “Stern” Gabriel Grüner, Volker Krämer, and interpreter Senol Aliti were killed on 13 June 1999 near Prizren.

Media Action International journalist Aleksandar Simović Sima was kidnapped on 21 August 1999 in Priština, and then killed.

The editor of RTV Priština, Krist Gegaj, was killed on 12 September 1999 in Istok.

Photojournalist Momir Stokuća was killed on 21 September 1999 in Priština.

Journalist of the Serbian newsroom of Radio Kosovo Marjan Melonaši disappeared on 9 September 2000 in Priština.

“Rilindja” journalist, Shefki Popova, was killed on 10 September 2000 in Vučitrn.

Journalist of the newspaper “Bota sot” Xhemail Mustafa was killed on 23 November 2000 in Priština.

Journalist of the newspaper “Bota sot” Bekim Kastrati was killed on 19 October 2001 near Priština.

Journalist and columnist of the newspaper “Bota sot” Bardhyl Ajeti was assassinated on 3 June 2005 near Gnjilan and died on 25 June 2005 in Italy.

“For more than two decades families have been left in the dark and those responsible for the killings, kidnappings and disappearances of our colleagues have never been held accountable. Still, to this date, no effective investigations have been held despite a raft of resolutions, pledges and declarations to put an end to impunity. It is time for the International Commission of Experts to investigate the killings, kidnappings and disappearances of journalists and media workers in Kosovo between 1998 and 2005,” emphasizes Anthony Bellanger, Secretary General of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

Missing investigations

In the evening of 21 September 1999, UNMIK police received a call that something terrible was happening in the family home of photojournalist Momir Stokuća, in the Peyton neighborhood in the center of Priština. When officers arrived, they found the side entrance door open. They found Momir’s lifeless body on the bedroom floor.

Stokuća was 50 years old when he was killed. A longtime associate of the daily newspaper Politika and a photographer of the weekly magazine Vreme, one of the few independent media in the early 1990s in Serbia, a passionate reader of books. He loved photography and he loved Kosovo.

Police investigation into his murder has never been done. The case was “lost” – and the police report on the murder “disappeared” from the UNMIK documentation. The Stokuća family was never called for an interview by a police officer or a prosecutor. There was no information about this murder in the documentation of Eulex, the Special Prosecutor’s Office of Kosovo, or of the Serbian War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office.

It is as if the crime never happened.

Murders, kidnappings and disappearances of journalists are crimes that occurred during the war in Kosovo between 1998 and 1999, and after the arrival of NATO forces and the United Nations (UN) in June 1999.

During the journalistic investigation, which also included an attempt to find out what happened with the police investigations of the murdered and missing journalists, the conclusion became obvious and devastating: the international forces in Kosovo did not make the necessary effort to investigate these crimes, whether the victims were Albanians, Serbs, Germans, or other nationalities.

They did not conduct effective investigations, nor did they take responsibility towards the rule of law and the victims’ families. There have been plenty of indicators that investigations have been hindered, but not enough voices to ask if there is any and what about institutional accountability?

That is why even today we do not know the identity of the killers and kidnappers. We only know that the perpetrators are at large, unpunished. We also know that it happened in Europe in our time.

The responsibility lies with all those who were in charge of the rule of law in Kosovo in the period from 1998 to 2005.

The investigation of murders, kidnappings and disappearances of journalists and media workers was under the direct mandate of the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), which had executive authority under Resolution 1244 until 2008. During that period, the police and judicial authorities were completely in the hands of the UN Mission in Kosovo.

Since 2008, the executive power of the rule of law, and thus the responsibility for the investigations and prosecution of crimes, has been in the hands of the European Union Mission for the Rule of Law (Eulex). From 2014, Eulex will hand over the executive mandate in the field of investigation and justice to the Kosovo authorities in stages.

As part of the journalistic investigation, international institutions in charge of or connected with the rule of law in Kosovo, responded that they did not have or did not know where the possible documentation related to crimes against journalists and media workers was located.

For example, when I, as a journalist in search of documents, took to UNMIK precise information with the file numbers under which UNMIK archived some of the cases of murdered and missing journalists – even then, the UNMIK staff was unable to find files or documents in the archive.

Finally, UNMIK will explain that those who are employed there today do not know what was done a few years ago and “for some reason, those who were responsible then did not do a good job”.

“Disappearance” of police reports such as the one related to the murder of Momir Stokuća was explained by the “change of duty and relocation” of UNMIK personnel.

The right to life

When someone goes missing, the competent police are obliged to open an investigation, take steps to find the person: they will talk to people the missing person knew, they will look at the available footage from surveillance cameras, they will take DNA samples…

The disappearance of Marjan Melonaši was reported immediately, in September 2000, to UNMIK, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Red Cross of Yugoslavia and the Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Serbia.

However, UNMIK opened the investigation only five years later. The police officer of the UN mission opened the investigation file with the name of Marjan Melonaši only in 2005, only to close it later the same day. The UNMIK police did not question anyone in connection with the disappearance of this journalist.

The lack of an effective investigation by the UNMIK police in the case of the disappearance of journalist Marjan Melonaši was described in detail in the opinion of the Human Rights Advisory Panel (HRAP). Explaining all the omissions, in its conclusion the Panel asks the Head of UNMIK to publicly admit responsibility for the violation of human rights, apologize to the family of Marjan Melonaši and ask the authorities in Kosovo to do everything possible to continue the criminal investigation and bring the perpetrator to justice.

The Human Rights Advisory Panel (HRAP) in Kosovo was established in 2006 in response to the human rights violations recorded by the UN human rights bodies, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW), and in response to the major criticisms that came from the Council of Europe (CoE) and the European Commission for Democracy through Law (the “Venice Commission”). The latter, in its Opinion of October 2004, highlighted a wide range of human rights problems under UNMIK’s administration in Kosovo.

The work of the HRAP was limited to examining complaints submitted by individuals or groups, essentially in response to complaints from families who felt that the UN Mission in Kosovo had not conducted adequate investigations into the murders and kidnappings of their loved ones. Apart from the family of journalist Marjan Melonaši, the families of journalists Aleksandar Simović and Ljubomir Knežević also contacted the HRAP.

In the opinions published from 2010 to 2016, the HRAP assessed that the complaints were justified; recommended to the Head of the UNMIK Mission to issue a public apology to the families and to ensure that Eulex continued the investigation. That did not happen.

Marek Nowicki, an internationally recognized lawyer in the field of human rights, during his career also engaged as an expert at the Directorate of the Council of Europe for Human Rights and the Venice Commission, and the former Chairman of HRAP, reminds that the right to life is a basic human right and that “its preservation also requires an adequate response in the event of a death and therefore prosecution, adequate and effective independent investigation to establish the circumstances and bring the perpetrators to justice”.

“These are elementary obligations in any case, and all the more so when it concerns a journalist.” Such an investigation should have been taken place as soon as UNMIK became aware of these facts. Today, after many years, obtaining the expected results is much more difficult, but not completely impossible. However, it requires a lot of motivation and effort”, Nowicki points out.

Concluding the Mission in Kosovo in 2016, the HRAP assessed that the complainants were victims of UNMIK’s actions on two occasions.

Nowicki, who was the international Ombudsman in Kosovo from 2000 to 2005, clarifies:

“They are double victims in the sense that they died at the hands of assassins and then their families became victims of the lack of an adequate response from the law enforcement authorities and, as a result, they have not – at least so far – received fundamental justice, accountability of the perpetrators of the crimes or any redress. They do not even know the circumstances of the killings”.

Wartime

On 21 August 1998, Radio Priština journalists Đuro Slavuj from Dvor na Uni and Ranko Perenić from Lipljan went to the Sveti Vrači monastery in Zočište to make a report on the return of the kidnapped monks. They have been missing ever since. The car they were in, the blue “Zastava 128”, was not found.

Afrim Maliqi, a journalist of the “Bujku” newspaper, was killed on 2 December 1998 in Priština, in the neighborhood of Sunny Hill. At the time of the murder, he was in a vehicle with two friends.

Enver Maloku, a journalist, writer and Head of the Kosovo Information Center (KIC), was shot on 11 January 1999 in the afternoon, a few meters from the apartment on the ground floor of the building in Sunny Hill, where he lived. He died soon after in a hospital in Priština.

These crimes took place before the arrival of NATO forces in Kosovo.

Journalist and President of the B92 Foundation Board of Directors Veran Matić has been the President of the Commission for Investigating Murders of Journalists in Serbia for ten years. Since 2018, that body has also been investigating the murders and disappearances of journalists in Kosovo that occurred in the period before the arrival of international forces.

“I had insight into the data of Serbian institutions on the murders of journalists and media workers in that period. The impression is that there were no investigations, the cases were only registered, there was a superficial police-court investigation at the crime scene, and nothing more. There are no data on some cases or I could not find them. To an extent, we managed to get hints of possible evidence, but institutional frameworks for effective investigations have not been established”, Veran Matić points out.

The long-time fighter for the safety of journalists underlines that “in general, there is no desire and will for our societies to deal systematically with the evil past, with crimes that were committed in our name, in the name of a certain people”.

“With such a policy, the strong rhetoric that everything will be investigated and criminals will be punished is actually false. The international community is complicit, and often more responsible than the conflicting parties for total impunity. UNMIK, Eulex and other international organizations, the EU, the USA and other powers engaged in the establishment of peace and new statehood in this area had every opportunity to deal more effectively with these investigations. Not only did they not do that, but also they permanently disabled making any steps forward. The UNMIK archive is not organized, it is located in several places. It is similar with the archive of the OSCE”, concludes Matić.

Apart from the missions whose main mandate is the rule of law, NATO, i.e. the KFOR Mission, was in charge of security in Kosovo. An important role was played by the International Civilian Office (from 2008 to 2012), which was led by the International Civilian Representative, Dutch diplomat Peter Feith. Even today, the Office of the European Union and the OSCE Mission play a significant role.

The OSCE verification mission, framed by the mandate of the UN Security Council Resolution 1199, arrived in Kosovo in October 1998.

Tanjug journalist Nebojša Radošević and photographer Vladimir Dobričić were kidnapped on 18 October 1998, when they went to meet the Head of the OSCE verification mission, William Walker, at the “Slatina” airport near Priština. They were released after forty-one days.

The power of the underworld

Famous journalist of “Rilindja” Shefki Popova was killed at his doorstep in his hometown of Vučitrn on 10 September 2000. The murder happened in the evening (at 22:15) when Popova was returning home. Witnesses saw two men running away.

The murder of Popova happened after the attempted murder (in June 2000) of journalist Valentina Čukić, editor of the Serbian-language program at Radio Kontakt in Priština.

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the world’s largest journalist organization, protested against the brutal killing of Popova and called upon all warring political factions in Kosovo to respect freedom of the press and stop attacks on journalists.

The IFJ also warned that the murder of the “Rilindja” journalist could lead to further attacks. After that crime, three more journalists were killed.

On the murder of Shefki Popova, Bardhyl Ajeti, a journalist of the “Bota Sot” newspaper, wrote numerous articles, appealing to find out who the killers were. Ajeti was killed in 2005.

Bekim Kastrati, a journalist of the newspaper “Bota Sot” was shot dead from an ambush on 19 October 2001, in the village of Lauš, northwest of Priština. Reporters Without Borders reported that the journalist was traveling in a car with two men when they were overtaken by a “jeep” from which they were shot.

In an OSCE survey in December 2001, 78 percent of journalists in Kosovo said they did not feel free to engage in investigative journalism.

“The murder of two Kosovo journalists – Shefki Popova and Bekim Kastrati, as well as cases of threats against other journalists investigating corruption, crime or drug trafficking, warn of the power of the underground in Kosovo. “A free journalist in Kosovo is a dead journalist,” says a local reporter. However, it is not only censorship by killing that is threatening media freedom in Kosovo, even in the situation where two journalists were killed, but the fact that such things can happen. Intimidation of journalists facilitates the control of newspapers and television broadcasters,” the OSCE stated in its report from June 2002.

For the next decade and a half, the topic of murdered and missing journalists would slowly disappear from the agenda of the OSCE Mission in Kosovo.

“In the period from 1998 to 2005 in Kosovo, we have the largest number of unsolved cases of murder and kidnapping of journalists. This is a devastating fact for the United Nations and the European Union and all the big powers, and of course for the Serbs and Albanians and our journalistic community. The liquidations of journalists were not treated as a drastic threat to freedom of speech and the media,” emphasizes Veran Matić.

Missions and declarations

“The OSCE office in Kosovo, when it was headed by Jan Braathu, did the most of all international organizations in the fight against impunity for crimes against journalists – from the conferences they organized, where the idea for an international commission to investigate the murders of journalists started, through great support for dialogue and research, as well as sensitizing the regional and international public on this topic. Unfortunately, I do not currently see that kind of focus and commitment in the current mandate of the OSCE Mission in Kosovo,” the President of the Commission for Investigating Murders of Journalists points out.

In December 2018 in Milan, the OSCE Ministerial Council adopted a Declaration calling for public and unequivocal condemnation of attacks and violence against journalists and taking effective measures to end impunity for crimes against journalists.

Norwegian diplomat Jan Braathu, who has been active in the region for more than 15 years, is today the Head of the OSCE Mission in Belgrade.

When he assumed the post of Head of the OSCE in Priština in 2016, the topic of murdered and missing journalists in the period between 1998 and 2005 was not on the Mission’s agenda. In general, he underlines “there was very little understanding of the role of journalists in conflict situations”:

“I raised the issue of murdered and missing journalists even prior to the OSCE Ministerial Council Decision, believing that the fight against impunity and the seeking justice are in accordance with the previous OSCE commitments and decisions, and that resolving these issues would in some way contribute to dealing with the past. However, there seems to have been a widespread opinion in Kosovo that the killed and missing journalists were in some way themselves parties to the conflict, implicitly that they were “spies” or politically engaged in some other way. There was also concern that raising these issues would prove to be politically controversial and were best left aside. Some argued that it is was not directly within the Mission mandate, that UNMK has been responsible. The latter is true, but still I believed that the issue of impunity and the OSCE commitments merited Mission engagement on the issue”, says Ambassador Jan Braathu.

Conferences on murdered and missing journalists were held in Gračanica and Priština on 4 and 5 December 2019, at the initiative of the Journalists Association of Serbia and the Association of Kosovo Journalists, with the support of the OSCE. Family members and friends of the murdered and missing journalists, as well representatives of international rule of law missions and journalist associations participated in the dialogue.

“It was the first time that families of victims from both sides, Serbs and Kosovo Albanians, sat together and spoke about their issues. At the same time, it was the first time that the issue had been dealt with so publicly. We heard the Kosovo prosecutor say that the cases are open for further investigation. That in itself was a breakthrough”, emphasizes Braathu.

He also adds “the Kosovo judicial authorities received files, many incomplete from Eulex, who in turn had received the same incomplete files from UNMIK”.

“The Kosovo authorities are now being asked to investigate and prosecute cases from before their institutions were established, from the time when Kosovo was fully under the UNMIK administration. The cases from 1998 were prior to UNMIK and thus directly under the judicial authority of Yugoslavia. It is a daunting judicial task even under optimal conditions.”

Ambassador Braathu, who has been working on the Western Balkan issues for more than two decades, underlines that he believes that learning the truth about the murders and disappearances of journalists in Kosovo from 1998 to 2005 is important for “dealing with the conflicted past and as part of the reconciliation process”.

“Impunity for one crime can encourage further crimes. The preventive aspect is central, also to war crimes trials. Families need to achieve closure, to know what happened to their loved ones, where their remains are and to bury them with dignity. I underline that the victims and their families are from both communities. In addition, there are the German Stern journalists, whose case seems to be in a limbo. I believe that the OSCE Ministerial Council Decisions were made to be implemented. If an issue is important enough to merit high-level ministerial negotiations and consensus decisions, they also merit follow-up in action,” concludes Ambassador Braathu.

When asked about the murdered and missing journalists in Kosovo between 1998 and 2005, the answer arrived from the office of the current OSCE Ambassador in Kosovo Michael Davenport that the Mission had already given all the information it could on this topic.

“We will, of course, continue to monitor this matter and support your continued efforts in this regard,” they added.

We are looking for them

In 2012, in the fight against oblivion, the Journalists Association of Serbia placed a plaque on the road between Zočište and Velika Hoča near Orahovac to the missing colleagues Ranko Perenić and Đura Slavuj, which reads in Serbian and Albanian: “Here on 21 August 1998, our fellow journalists were kidnapped. We are looking for them”.

The plaque was torn down eight times and was placed for the ninth time in May 2022. Only once did the Kosovo police find the culprit who stated that the crime was ethnically motivated.

The defendant admitted that he used an excavator to tear out the plaque dedicated to the kidnapped journalists and his motives. He was sentenced to pay a fine of 200 euros.

“The last time it happened, we did not contact the police, but they certainly saw it in the media. Inside the Association, we thought that after the demolisher of the eighth plaque was discovered and convicted, no one would demolish anymore, but, unfortunately, it continued. However, we will not give up on placing a plaque at that place, no matter how many times someone demolishes it”, Budimir Ničić points out, who was the President of the Journalists Association of Serbia in Kosovo for seven years.

Ničić, a long-time journalist from Čaglavica, recalls that ever since the plaque was installed at the place where Ranko Perenić and Đuro Slavuj were last seen, journalists gather every year on the occasion of the anniversary of their disappearance:

“Every 21st August, colleagues from Belgrade and Kosovo are at that place, and it is good that there is solidarity and efforts by journalists to finally solve this and other cases of kidnapped and murdered journalists. What happened to them can happen to each of us, and that is why it is important that we stand in solidarity in this fight”.

During his mandate in Kosovo, Ambassador Jan Braathu was the only foreign diplomat who came to support the families and gathered journalists.

The fight against impunity

The road to justice is long and burdened with all the problems arising from war, irresponsibility of international missions, failure to face the past and impunity. All things considered, will we ever get to the truth and punishment for the crimes committed?

“Undoubtedly, all efforts should still be made. However, with no guarantee that the truth and the perpetrators will ever be found”, answers human rights lawyer Marek Nowicki.

Every bullet fired at a journalist is an attack on basic human rights, democracy, freedom of speech and freedom of information. Behind every unsolved murder, after all these questions we have asked the authorities, one more question remains – what have we, colleagues and journalists, done to stand in the way of impunity?

In May 2018, the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) adopted a resolution on investigations into the murders of journalists in Kosovo, at the suggestion of the Journalists Association of Serbia (UNS), the Association of Journalists of Kosovo (AGK), the Independent Journalists Association of Serbia (NUNS) and the Union of Journalists of Serbia (SINOS).

Unfortunately, there was no reaction that would bring justice to the families of the murdered and missing journalists, and bring the criminals to justice. There was no effective investigation even when most of those cases were included in the platform of the Council of Europe for the protection of journalism and the safety of journalists in August 2018.

At the same time, there is no shortage of resolutions, declarations and appeals in paper for the safety of journalists, especially when it comes to their right to work in conflict situations.

For example, UN Security Council resolutions condemn violence and abuses committed against journalists and media workers in the situations of armed conflict, emphasizing international obligations to end impunity and prosecute those responsible for these serious violations of international humanitarian law.

UN Security Council Resolution 1738 from 2006 specifically reminds the signatories of the Geneva Conventions that they have an obligation to seek and try persons who are alleged to have committed or ordered serious violations of these conventions to be committed.

UN Security Council Resolution 2222 from 2015 reaffirms that the parties to an armed conflict bear the primary responsibility to take all possible steps to ensure the protection also of those “who exercise their right to freedom of expression by seeking, receiving and disseminating information in various ways”, in accordance with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and futher emphasizes the obligation of parties to conduct impartial, independent and effective investigations and to bring the perpetrators of such crimes to justice.

Bearing in mind that the fight against impunity for crimes against journalists and media workers is crucial and essential for the service of justice, but also necessary for the further protection of media professionals, as well as that bringing those responsible for those crimes to justice is a key element in preventing future attacks, the Assembly of the European Federation of Journalists (at the proposal of the Journalists Association of Serbia), requested the formation of an international expert commission as soon as possible that would investigate the murders, kidnappings and disappearances of journalists and media workers in Kosovo in the period from 1998 to 2005.

The EFJ Resolution was voted in 2021 in Zagreb. Again – there is no progress in the investigations.

Ambassador Jan Braathu points out that “the EFJ Resolution is another turning point”:

“Establishing an international commission is a big undertaking, and a lot of work needs be done by EFJ and journalists’ associations in order to implement this Resolution.” I do not know if the EFJ has actively advocated in the United Nations, with the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, national governments such as Great Britain, that speak about the safety of journalists issues? The Commission will not happen by itself and I understand the EFJ Resolution as a call to action”.

Veran Matić, President of the Commission for Investigating Murders of Journalists in Serbia, points out that when we talk about an international commission, we are also talking about the collection of data from all relevant sources, their analysis, conception, conducting investigations, direct engagement of authorities from Serbia and Kosovo, and the opening of all archives of international forces in Kosovo, because everyone took their own with them:

“It is a great responsibility and danger for those who would deal with it. There are more deterring motives. However, that is the only possibility, because neither Belgrade nor Priština are ready to deal with this topic in a committed manner. The commitment of international institutions to hire the best investigators, forensics and journalists in order to concentrate energy and gather knowledge from all sources would be the basis for progress in investigations.

Marek Nowicki, a human rights lawyer, reminds of the fact that for the formation of such a body, many prerequisites must be met:

“One might be inclined to do so, although its success would require the fulfilment of many difficult conditions, including legal ones, concerning, inter alia, the consent of the Kosovo authorities, the manner of its establishment, the status of the members of such a Commission, access to documents of the agencies of the various states and organizations involved in Kosovo, including those covered by the confidentiality clause, the legal significance of its conclusions, etc. The output of a purely civic body would necessarily have to be limited”:

Serbeze Haxhiaj, an investigative journalist and news editor in Kosovo, who has been dealing with corruption, human rights, security issues and war crimes for years, also points out the challenges for creating such an international commission:

“It is a very important step of the EFJ. In many cases and countries, local justice mechanisms could not do their job properly due to political pressure and ethnic sentiments. However, because of the time that has passed, many witnesses are no longer alive or their memory is not what it was before, and it will be difficult for any commission or prosecution to shed light on those cases. However, the EFJ can put more pressure on local authorities to do their duty and give priority to investigating the cases of murdered journalists, punishing such crimes and eliminating their consequences”.

Journalist Budimir Ničić points out that the investigation of these crimes was primarily the job of the institutions:

“But since they have not done it for more than 20 years, I assume that something is seriously wrong, or they are incompetent, or they do not want to do it. Certainly, an independent international commission made up of representatives of journalists, among others, would contribute, if not to solving the cases, then certainly to clearly find out who is specifically responsible for the fact that these cases have not been solved so far”.

The International Federation of Journalists reminds that they worked on raising awareness and implemented a campaign asking the international community to do more to bring those responsible for crimes to justice.

“We highlighted these cases as emblematic during our annual campaign to mark the International Day to End Impunity, alongside a call for establishing an independent commission which can investigate, enable proceedings against those responsible and pave the way for justice and compensation. We remain committed to achieving justice and are exploring all avenues within the international system to ensure that the cases of our colleagues will not be forgotten,” said Anthony Bellanger, Secretary General of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

Building peace

“For many journalists in Kosovo who witnessed the loss of their colleagues, it remains very important to know the truth about their murderers and to see justice to be served. But, as it happened in other former Yugoslavia countries, being louder in seeking justice for journalists, especially those from another ethnicity, still remains something they cannot say freely because of the inter-ethnic animosities inherited from the war. Those killings of journalists, despite the fact of ethnicity, have soared fear among journalists and made the environment of doing journalism even more hostile”, emphasizes Serbeze Haxhiaj, an award-winning journalist who has written numerous articles on the subject of murdered and missing journalists in Kosovo for the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network – BIRN.

Punishing criminals is undoubtedly justice for the victims and peace for their families, it is important for the freedom of the media, freedom of speech and the overall sense of safety of journalists. Can we say that it is also important for building peace?

“As long as justice has not been served and families of victims don’t know the whole truth, it will continue to be a heavy burden on the media landscape and for freedom of speech. This is a key element for a lasting peace and reconciliation process. Furthermore, the commitment to investigating the murders of journalists and pressure in the press is a vital clue on whether the country is beginning to backslide in terms of its commitment to wider human rights protections”, says Serbeze Haxhiaj.

“Of course it’s important”, journalist Budimir Ničić answers the same question, “because living with the fact and the feeling that there might be a criminal in your neighborhood is not pleasant at all”:

“Considering so many unsolved cases not only of journalists, but also of other people who have been kidnapped or killed, it means that those responsible for these crimes are still at large and are in our environment and society in general. If those who could kill and kidnap people who were just doing their journalistic work, as well as other innocent people, are at large, then no one can be at peace, regardless of whether they are Serbs or Albanians. Also, I believe that no one wants to live in a society where criminals walk freely, and that’s why I think that the entire Kosovo society should be more active in solving these cases, regardless of religions and nations the victims or criminals belong to”, concludes Ničić.

“The safety of journalists is fundamental for a democratic society living in peace “, human rights lawyer Marek Nowicki underlines:

“To quote the European Court of Human Rights, which emphasized that “States are obliged to create, while establishing an effective system of protection for authors or journalists, an environment conducive to the participation in public debates of all persons concerned, allowing them to express their opinions and ideas without fear, even if these run counter to those defended by the official authorities or by a significant part of public opinion, or are even irritating or offensive to the latter”. This principle also implies, among other things, the obligation to effectively prosecute and punish perpetrators of attacks on journalists”.

The President of the Commission for the Investigation of Murders of Journalists, Veran Matić, reminds that “it is precisely because the national elites in the entire Balkans do not solve the problems arising from the wars that we have the extension of those wars by other means still today”:

“If our societies are not aware of the crimes committed, including the murders of journalists, if there is no sincere joint search for the missing, if there is no clear condemnation of every crime, violence, if there is no dismantling of the ideologies and policies that led to wars and brutalized those wars, then situations like this will happen in which not only is there no empathy, but the ideas that justify everything that was done in the name of one’s own nation prevail in the public”.

“It is disastrous”, Matić underlines, for “the healing of each of our societies, democracy, the rule of law, but also for regional and world peace, which he sees from the reactions of our societies to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine”:

“That is why the disclosure of all the facts related to the kidnappings and murders of journalists would be very important. Reports of what has been discovered are already important developments. Punishment depends on sufficient evidence required by the court. Even if there were no trial and punishment, the fact that everything possible was done would be a big step forward. And a sign that it is inadmissible to kill journalists and that at some point it will be found out who ordered and did it. It is the most effective form of prevention”.

Journalist Jelena L. Petković did research on murdered and missing journalists in Kosovo in the period from 1998 until 2005. Part of that material was published within UNS research.